The manuscript has long had a special place in the diverse cultures of Southeast Asia. The British Library’s collection includes a whole range of manuscripts from the region, including examples from Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Lao, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia.

In the Asia House friends tour ‘the Art of the Book in Southeast Asia’, three British Library curators gave us an exclusive tour of the Library’s collection of Southeast Asian manuscripts. Many of the manuscripts in the collection are sacred texts, but other would have been used for fortune telling, as instruction manuals or simply for storytelling.

Although 90% of manuscripts produced in Southeast Asia would not have been illustrated, the cream of the British Library’s collection features lavishly decorated texts. Like proud parents, the curators fondly introduced us to the jewels of the collection.

Manuscripts from Thailand, Burma, Malaysia and Indonesia had been specially laid out for us to view on a long table in a quiet room. The manuscripts from Burma pack the most powerful visual punch. Every Burmese manuscript was “complete with exquisite illustrations”.

The curator for Burmese manuscripts talked us through a record made by the Burmese King recording his generosity to a Buddhist monastery. Instead of pages of lists and text, the manuscript is pictoral. It provides an illustrated record not only of the goods given, but the artist’s rendition of the presentation ceremonies. It is amazing that a picture book with perhaps just a single word inscription could be an official record for the Palace archives, yet this astounding use of images shows just how powerful illustration can be.

Another fascinating feature of Southeast Asian manuscripts is the use of the folding book, a method of book-binding commonly found in Burma and Thailand. Folding books are particularly useful for illustrated manuscripts as they allow for the manuscript and all the illustrations to be viewed in full.

State sponsorship of Buddhism in Burma and Thailand meant that new monasteries were established and many hand-written Buddhist manuscripts commissioned. These manuscripts, the curators explained, would not have been read or owned privately. “Access to the actual books was very privileged” and Buddhist manuscripts such as the ones on display at the British Library would have been used primarily by monks.

Often written in ‘sacred’ scripts, such as the defunct Khmer language in Thailand, the content of the manuscripts would have been incomprehensible to most lay people. Instead, the monks would chant the texts aloud. Today, the monks chant the texts and then explain and discuss the contents with the lay.

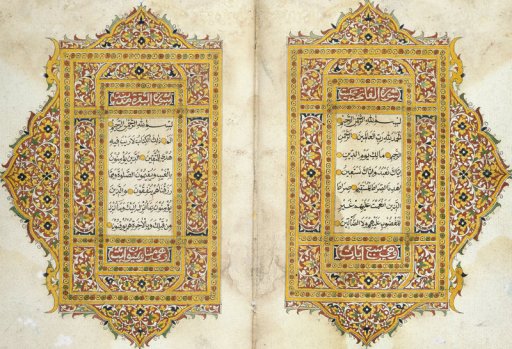

Before talking us through the Malaysian and Indonesian manuscripts, the curator for this region modestly assured us that those from this area do not visually compare with those from Thailand or Burma. There was no such inferiority however in the gravity and grace of the two Qu’ran she showed us. The first was completely plain; its only adornment the elegant flow of Arabic spilling across pages of imported European paper.

Although the Qu’ran does exist in translation, it is only considered to be the true word of God in the language to which it was revealed to the Prophet Mohammed – Arabic. The written language is breathtaking in its beauty; with no punctuation or capitals, Arabic calligraphy is a common decorative feature throughout the Muslim world.

The second copy of the Qu’ran was a departure from the quiet simplicity of the first example. Each page had been painstakingly illuminated with intricate patterns and finished with ink made from powdered gold. In many Islamic cultures, the depiction of living things is avoided in art, particularly in a religious context. The result of this is that pattern has emerged as favoured means of decoration.

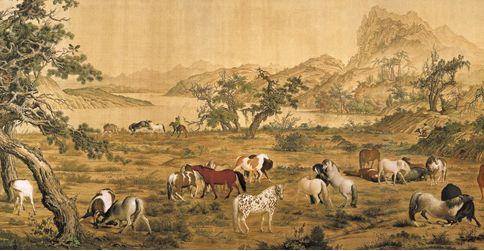

Only Java has the tradition of figurative illustration in the Malaysia-Indonesia region. The spiky figures shown in the manuscripts were modelled on traditional shadow puppets. The Javanese examples we were shown were story books, filled with pictures of kings and packed with jokes. One of these was a pristine manuscript produced in 1804. It was a copy made for the wife of a Dutch official it and has very clean and unused air.

Another manuscript sat alongside it; despite its earthy appearance this second manuscript is considered to be the “finest example of the genre”. Dating to the 1700’s, this manuscript is a “really loved and well-used manuscript” with an illustration on “every single page to make you laugh”. Grubby and well-thumbed, it is easy to imagine this as a favourite book brought out and recited from at evening gatherings.

The makers of Southeast Asian manuscripts were remarkably creative in the materials and techniques they used. Palm leaf has long been the standard writing material of Southeast Asia. The curators told us an old story of a young Southeast Asian girl who wrote a love letter on a young palm leaf, rolled it up and wore it as an earring until she was able to safely deliver it in secret.

Writing on palm leaf is a specialist skill. Instead of using ink and a pen or brush to write directly onto the surface of the leaf, the writing would have been incised into the surface with a stylus and then a black ink solution wiped into the incised marks.

Paper made from mulberry trees was also used for manuscripts. Mulberry paper had several benefits; it is stronger and lasts longer than ordinary paper and is less susceptible to damp. Its durability also meant that mistakes could be scraped off.

Tropical conditions make the preservation of manuscripts very difficult; many manuscripts being damaged or destroyed by “heat, damp, insects and, in wooden homes, fire”. However, pepper and cloves are used locally as natural preservatives to help keep away insects. The use of these spices with the addition of a wrapping cloth is an effective traditional conservation method.

The curators told us about a manuscript from central Sumatra that has recently been subjected to scientific testing to determine its age. As it was written on tree bark paper, researchers were able to to date the manuscript to the 14th century. A manuscript of this age is extremely rare in Southeast Asia and this astounding manuscript was able to survive so long due to the unique way in which it was stored. For generations, it was carefully kept in the house allocated to the head of the community. It was wrapped in spices and aired once a year at an annual viewing ceremony. Kept in a loft space over the kitchen, the smoke from the kitchen fire acted as a further preservative allowing the manuscript to survive for centuries.

This tour of the British Library’s collections opened our eyes to the extraordinary variety found among the manuscripts of Southeast Asia. The vibrancy and detail of the illustrations reveals Southeast Asian manuscripts are true works of art. These works can still entertain, inspire and through their well-thumbed pages, provide a connection between the past and the present.